On

June 25, 1876, at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, five companies of the U.S.

Seventh Cavalry, under the direct command of George Armstrong Custer were wiped

out.

This

was not the first time that the U.S. military had suffered a calamitous defeat at

the hands of the Plains Indians. On

December 21, 1866 Captain William J. Fetterman and eighty men under his command

were similarly annihilated near Fort Phil Kearny in Wyoming. There are some striking similarities between

the two battles.

In

June 1866, Colonel Henry B. Carrington

was ordered to build several forts along the Bozeman Trail to protect emigrants

on their way to the Pacific coast.

He established three forts along the trail, including his

headquarters at Fort Phil Kearny, near present-day Buffalo, Wyoming some 90 miles south the Little Bighorn

battlefield.

During the next few months, while Fort Phil Kearny was

being built, Carrington suffered 50 attacks from Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors, losing more than 20 dead.

Although Carrington had served in the Civil War,

providing valuable service in both intelligence and recruiting, he had never

seen battle. He went about fulfilling

his mission cautiously. Too cautiously

in the view of some of his junior officers who urged him to take the offensive.

Grumbling increased after November 3, when 63 men,

including infantry Captain William Fetterman arrived to reinforce the

fort. Although he had no experience

fighting Indians, Fetterman criticized Carrington's timidity and expressed

contempt for the Indian foes. He boasted, "Give me 80 men and I can ride

through the whole Sioux nation.” This

comment is strangely reminiscent of George Armstrong Custer’s boast, “There are

not enough Indians in the world to defeat the Seventh Cavalry.”

Fetterman was a combat veteran of the Civil War and had been

promoted to Brevet Lt-Colonel by the end of the war. Many Civil War officers, including Custer, did

not seem to realize that incurring high casualties was not an indication of

good tactics. Frontal assaults and dashing charges were commonplace.

The Plains Indians,

on the other hand, rarely charged a stout defense. They hit the rear and

flanks, probing for weaknesses and creating disorganization and panic by using

mobility. They avoided heavy casualties whenever possible.

By

December 1866, Colonel Carrington had been pressured into being more

aggressive, despite the inadequacy of his troops. Carrington’s guide, the famed Mountain Man

Jim Bridger summed up the situation, "These soldiers don't know anything

about fighting Indians."

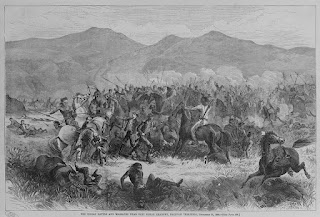

On December 21, 1866, a group of Indians, including Crazy

Horse, a later hero of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, were chosen to lure the

soldiers to their destruction. Just as

at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, a Lakota Sioux spiritual leader

prophesied victory. The Lakota saw this as the good medicine that won the

battle.

At about 10 am, on December 21, 1866, Colonel

Carrington sent a party to gather timber for the construction of the fort. Within an hour the timber party was under

attack. Carrington ordered a relief party composed of 49 infantry and 27 cavalry

troopers, and a few hangers on, to go to the rescue of the timber party. Claiming seniority as a brevet lieutenant colonel, Fetterman asked for command of

the relief party. Lieutenant George W. Grummond, a known critic of Carrington,

led the cavalry.

Carrington’s orders were clear. "Under

no circumstances" was the relief party to "pursue over the ridge that

is Lodge Trail Ridge". This differs

significantly from the orders Custer received from his commander Brigadier General

Alfred Terry which gave Custer great discretion in his actions.

Custer’s Last Stand: Portraits in Time

No comments:

Post a Comment