The Last Stand

Six months after the battle of the Little Bighorn (June 25,

1876), Frederick Whittaker’s A Complete Life of General George A. Custer was published. Whittaker’s book

was a canonization which presented Custer as a dashing and brilliant military

leader abandoned to his fate by lesser, disloyal, treacherous, and cowardly men. Whittaker borrowed

generously from Custer’s own book My Life on the Plains, as well as on his

own imagination, which was fulsome, since Whittaker was a professional writer

of nickel and dime novel fiction for a leading publisher.

The

Indians met the men under Custer’s immediate command about six hundred yards

east of the river. The Indians drove the

soldiers up the hill, and then made a circuit to the right around the hill and

drove off or captured most of the horses.

The troops made a stand at the lower end of the hill, and there they

were all killed. Whittaker’s source is

the New York Herald of October 6,

1876 which published the deposition that Kill Eagle, one of the hostiles, gave

to Captain Johnston, Acting Indian Agent.

Citing

an “officer of the general staff who examined the ground” as his source,

Whittaker describes the Custer fight in detail.

Custer was driven back from an unsuccessful attempt to cross the stream

to successive stands on higher ground.

Three quarters of a mile from the river Calhoun’s company is thrown

across the line of retreat. Whittaker

(who perhaps had the powers of a psychic medium) puts these words into Custer's

mouth, “The country needs; I give her a man who will do his duty to the death:

I give them my first brother (First Lt. Calhoun was the husband of Custer’s only sister). I leave my best loved sister a widow, that so

the day may be saved.”

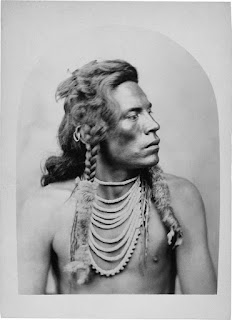

James Calhoun

Whittaker

continues, “So they stood till the last man was down…and then came the friendly

bullet that sent the soul of James Calhoun to an eternity of glory. Let no man say that such a life was thrown

away. The spectacle of so much courage

must have nerved the whole command to the heroic resistance it made. Calhoun’s men would never have died where

they did, in line, had Calhoun not been there to cheer them. They would have been found in scattered

groups, fleeing or huddled together, not fallen in their ranks, every man in

his place, to the last. Calhoun, with

his forty men, had done on an open field, what Reno, with a hundred and forty,

could not do defending a wood. He had

died like a hero, and America will remember him, while she remembers heroes.”

(Whittaker, 597)

Whittaker

continues, “…every man realized that it was his last fight, and was resolved to

die game. Down they went, slaughtered in position, man after man dropping in

his place, the survivors contracting their line to close the gaps. We read of

such things in history, and call them exaggerations. The silent witness of

those dead bodies of heroes in that mountain pass cannot lie. It tells plainer

than words how they died, the Indians all around them, first pressing them from

the river, then curling around Calhoun, now round Keogh, till the last stand on

the hill by Custer, with three companies.” (Whittaker, 597-8)

Whittaker now turns to the testimony of one of the Indian scouts, Curly,

who claimed to have escaped from the field of battle. (In 1886, Gall, a war leader of the Hunkpapa

Lakota, claimed that Curly knew nothing about Custer’s last moments, ”He ran

away too soon in the fight”).

Curly

According

to Whittaker, however, when Curly saw that the party with Custer was about to

be overwhelmed, he begged Custer to let him show him a way to escape. “…Custer looked at Curly, waved him away and

rode back to the little group of men, to die with them.” Why, Whittaker asks, did Custer go back to

certain death? “Because he felt that

such a death as that which that little band of heroes was about to die, was

worth the lives of all the general officers in the world….He weighed, in that

brief moment of reflection, all the consequences to America of the lesson of

life and the lesson of heroic death, and he chose death.” (Whittaker, 599-600)

Elizabeth Custer with President Taft

Whittaker’s biography of Custer molded the public’s perception

of George Armstrong Custer for over fifty years, because it was endorsed and

defended by Custer’s widow and her powerful friends and

allies. Elizabeth Custer was widowed at the age of thirty-four and

spent the next fifty- seven years, until her death in 1933, glorifying and

defending her husband’s reputation. Only after her death did

historians begin seriously re-examining the Custer legend.

Since his death along the bluffs

overlooking the Little Bighorn River, in Montana, on June 25, 1876, over five

hundred books have been written about the life and career of George Armstrong

Custer. Views of Custer have changed over succeeding generations. Custer has

been portrayed as a callous egotist, a bungling egomaniac, a genocidal war

criminal, and the puppet of faceless forces. For almost one hundred and fifty

years, Custer has been a Rorschach test of American social and personal values.

Whatever else George Armstrong Custer may or may not have been, even in the

twenty-first century, he remains the great lightning rod of American history.

This book presents portraits of Custer and the Battle of the Little Bighorn as

they have appeared in print over successive decades and in the process

demonstrates the evolution of American values and priorities.

Success leaves clues. So does failure. Some of

history’s best known commanders are remembered not for their brilliant

victories but for their catastrophic blunders.